tube will pass through the nasal cavity of most dogs a 5-Fr.

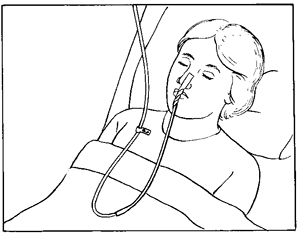

Polyurethane tubes (with or without a tungsten-weighted tip) and silicone feeding tubes may be placed in the caudal esophagus. The reason for this is that gastric acid will reflux back into the distal esophagus if a tube is holding open the lower esophageal sphincter, causing esophagitis. Indwelling NE tubes are placed to end in the distal third of the esophagus, not in the stomach (hence, the term "stomach tube" is not used). General anesthesia or tranquilization is not necessary to place an NE tube, therefore these tubes provide enteral access to patients considered anesthetic risks. nasogastric tube for contrast radiography). Other indications for placement include delivery of fluids or liquid medications and diagnostic testing (e.g. Nasoesophageal tubes are occasionally used to feed a patient for several weeks, such as some cats with liver disease. Nasoesophageal (NE) tubes are generally placed to feed cats or dogs that are anticipated to need feeding for less than a week, such as for patients with head trauma that may be unable to eat initially or to precede placement of a more durable tube. Nasoesophageal tubes are used most frequently to provide enteral nutritional support. Tube placement should be in the most proximal functioning portion of the GI tract possible via the least invasive method. Pharyngostomy tubes are no longer recommended due to the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Nasoesophageal, esophagostomy, gastrostomy or enterostomy are potential tube placement sites. An indwelling feeding tube is the method of choice if enteral feeding is necessary for more than two days. Neonates appear to tolerate multiple oral tube feedings daily better than adults. Orogastric tubes require placement at each feeding but may provide a useful option for one to two days of feeding. Appetite stimulants may be used successfully to induce food consumption in some patients (cyproheptadine 1 mg/cat/day or mirtazapine 1/8-1/4 of a 15 mg tablet/cat q72 hrs.) With each of these techniques, the amount of food consumed must be closely monitored to be certain it approximates the animal's RER. The first attempt is usually to offer a choice of palatable foods, followed by assisted oral feeding by hand or syringe. There are several methods of enteral feeding. When enteral access cannot be safely acquired for several days, parenteral nutrition can be used initially. Nutrients must be administered parenterally when the small intestine is not functioning sufficiently well to meet the patient's nutrient requirements enterally. Enteral feeding is preferred to parenteral feeding, whenever possible, because using the gastrointestinal tract is less expensive, stimulates the immune system and avoids most metabolic complications.

Nutrients can be supplied either enterally or parenterally. Enteral infusion of even small quantities of a liquid diet (microenteral nutrition) has proven beneficial in preventing intestinal mucosal deterioration during parenteral nutrition in piglets and in human infants and adults Translocation of enteric bacteria may occur across a compromised intestinal mucosal barrier.

Fasting for longer than three days results in enterocyte deterioration and decreased gastrointestinal immunity. As in human medicine, malnutrition in veterinary patients is thought to increase morbidity and mortality.Īny sick dog or cat with voluntary food intake significantly below the calculated daily resting energy requirement (RER) for more than three days is a good candidate for assisted feeding. Loss of more than 25 to 30% of body protein compromises the immune system and muscle strength, and death results from infection, pulmonary failure or both. Survival rates of human patients have been directly correlated with available muscle mass. In chronic illness, loss of muscle mass is commonly observed before serum protein levels become subnormal because muscle wasting is less life threatening than decreased serum protein concentrations. The major consequences of malnutrition are decreased immunocompetence, decreased anabolism, and altered intermediary drug metabolism. Instead of viewing anorexia as a secondary problem that will improve when the primary disease has resolved, it is now well recognized that it is better to be proactive and administer nutrients early.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)